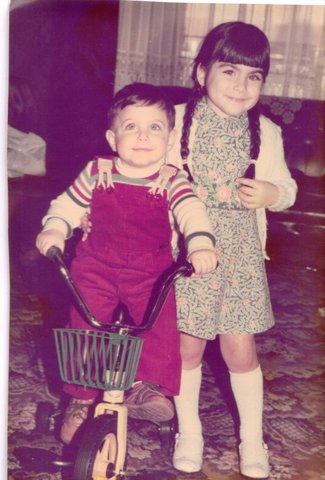

Born and raised in London, Ihsan Rustem has always had boundless intensity, energy, and curiosity. His parents wanted their son and daughter not to lose their Turkish Cypriot roots, “but they wanted to give us every opportunity that England had to offer, without restriction. We grew up with the best of both worlds and cultures,” naturally bilingual. Ihsan says he spoke English with his mother, who had come to England from Cyprus at the age of 5 and Turkish with his father who was 12 when he arrived, both around 1964 when Turkish-Greek wrangling over the island was at its height.

Now Ihsan is fluent in English and German, speaks fairly good Turkish, “can get by” in Dutch and understands a bit of French. He has very close ties to Turkey, less so to Cyprus. His grandmother lives half the year in Istanbul, and he’s done a lot of work in Istanbul, including with the Istanbul State Ballet, whose studios are on the Asian side. One day, after a 13 year absence from the city, he says, “I was standing in Taksim Square, in the middle of a city of 14 million people, with all those languages, bustling, people, noise, and all of a sudden I felt at home, calm.” The experience was the inspiration for his piece, Mother Tongue, for Portland’s Northwest Dance Project, for which he has created several works and where is now their Resident Choreographer.

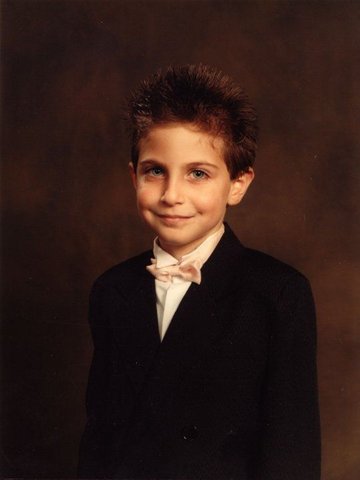

When I ask Ihsan how he came to dance, he says with his engaging smile, “It was a funny little path. I was interested in everything. I liked school and exploring and spoke easily to strangers—scared the hell out of my parents! At 6, I started to learn the violin—I didn’t want to then, but am grateful for it now. It came naturally and I was always told I had a good ear (something I found very bizarre until I understood many years later that they weren’t actually talking about my ears!).” In describing his life, Ihsan often speaks of things that are important to him now, but that he didn’t recognize as such at the time. Starting karate at 9, he got a black belt and “competed everywhere. I loved the discipline and the technical elements, and also the artistic aspect.” He always seemed attracted to that.

After primary school he was fortunate enough to attend the Thomas Tallis School in Greenwich, “Just a normal rough and tumble comprehensive—it really was the most amazing school,” Ihsan says, “a very artistic school, with even a boys’ dance group. I hated rugby and loved dance. I would hang out at school. It was fabulous!…. I got everything from that school. So much support and creativity. They nurtured and fostered creativity and individuality…. I owe everything to those teachers.” One of them, Deborah Kahn, who had been a dancer, gave him a leaflet on the National Youth Dance Company (now affiliated with Sadler’s Wells) and said, “Go audition.”

So at 14, he did. Before the audition, he decided that he needed to buy ballet shoes, tights, dance belt, etc. “to look the part.” He’d never been in a classical ballet class before, and “blagged my way through the barre okay by watching the feet of the person next to me,” but in the center, “they all went to the right and me to left.” The contemporary class was no better. For the solo part, “I thought I had nothing to lose.” And somehow, as a result of what he did there he guesses, he got to the 2nd round 2 weeks later. “Same story. I was by far the worst there.” Afterwards they asked how old he was. He had lied about his age. “You’re not 16,” they insisted, and he admitted he was two years younger. “Okay, look,” they said, “come as an apprentice, we’ll give you that opportunity.” They saw that he was very quick and musical, and would respond well to training, which he did.

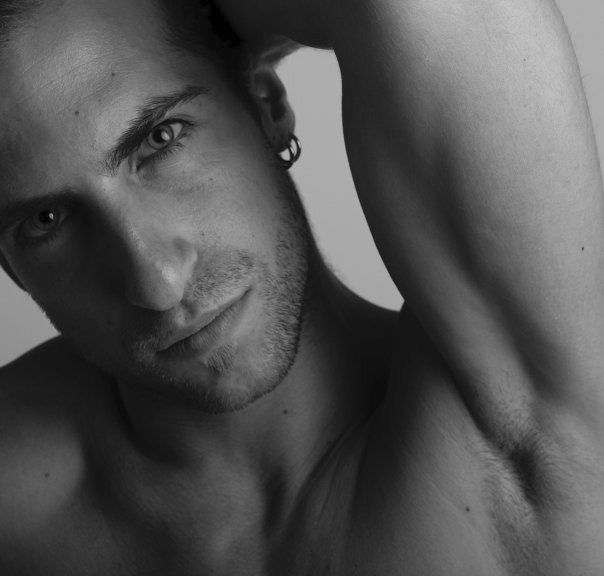

Of the 14 dancers let in, 9 of them had come from the Rambert School of Ballet and Contemporary Dance. After almost a year with the National Youth Dance Company, Ihsan went in May to Rambert and asked to audition. “But the auditions finished in February,” he was told. He persisted, however, and to make a long story short, they let him in. “I’d never do that now,” Ihsan says. Such ignorance is bliss. At Rambert Ihsan got very solid training. A year later he did an audition for Matthew Bourne’s Adventure’s in Motion Pictures—“just to practice”—and got a contract. “All much faster than it should’ve been,” he says. At some point later on, Ihsan met the Youth Dance company director and asked, “Why did you take me?” His potential and his eyes, he was told. His eyes certainly do compel attention. One interviewer (Armando Braswell of the Interview en l’air blog) remarks that they “look like multi colored glass. You can’t really say what color they are… They are very striking.”) “My eyes tend to change color depending on how tired I am,” Ihsan himself says, “and people get weirded out. But helped me get a job.”

If asked when he first began thinking about making dances, Ihsan replies, “Very early. I was first encouraged as a part of the boys’ group at that school, aged 11 or 12.” Rambert also offered many opportunities to create. After that he was always with companies that fostered new works through their annual choreographic workshops. “I’ve been very lucky,” Ihsan says. “None of it was planned, I always fell into the right hands—I worked my ass off, it’s true, but I’ve also been very lucky in where I landed.” Yet falling into the right hands and even hard work are not the whole story. Ihsan knows what he is doing and has matured considerably from the eager young novice who blundered into opportunity.

Since he had choreographed almost as long as he’d danced, I wondered what led him to stop the latter to concentrate on the former in the last few years. “I always said I wanted to stop when age and injury were not a factor,” was his answer. “It’s sad seeing fossils on stage. I stopped at my absolute best. I’d had fantastic opportunities, dancers to work with, lots of challenges, so many kinds of choreographers. I had a bucket list of ones I wanted to work with and got to do it. I was content with what I’d done.”

The decision came slowly, though. He won prizes, saw a whole new path opening up. “People responded to my work. At the time, I was dancing full time, a typical European 13-month contract with pension and holidays. I was very fortunate, I got leaves of absence, but bigger choreographic opportunities were presenting themselves that I didn’t have time for, and I didn’t want to get bitter. It took a few years to stop. When I finally did I had a whole season planned ahead with commissions. Very calculated. My last performance was with the Tanz Luzerner Theater and was choreographed by Patrick Delcroix, my ex-partner (and now best friend) in a 50 minute piece—it was the right piece to finish with. I’ve never missed being on the stage for a moment, I don’t need to be in spotlight.” It is the joy of creation, of dance, whether inventing or performing it.

Ihsan first came into contact with Whim W’Him artistic director Olivier Wevers via Northwest Dance Project. Ihsan had created a piece in 10 days, then Patrick Delcroix came back to stage it for the premiere, so Patrick met Olivier in person, but Ihsan still had not. He was in touch with Olivier on Facebook etc. over the years, however, and they’d spoken about working together. “I feel I know him,” says Ihsan. “When we write it’s very familiar, not formal.” So he was excited to hear about the Whim W’Him Choreographic Shindig 2015. “I would have wanted this opportunity as a dancer. It’s very precious.” He applied and was chosen by the dancers themselves from over 90 entries as one of 3 choreographers—along with Maurya Kerr and Joshua Peugh—for the program which opens the 12015-16 Inside Out season on September 11, with 7 performances at Capitol Hill’s Erickson Theatre.

What sorts of themes attract Ihsan as a choreographer? “I am very drawn by personal experiences, born out of where I am.” He’s done only one narrative piece and didn’t like it. But his works are “not abstract as such,” either. “I take a very emotional approach.” He wants to get every dancer on board and to view the process from their own perspectives.

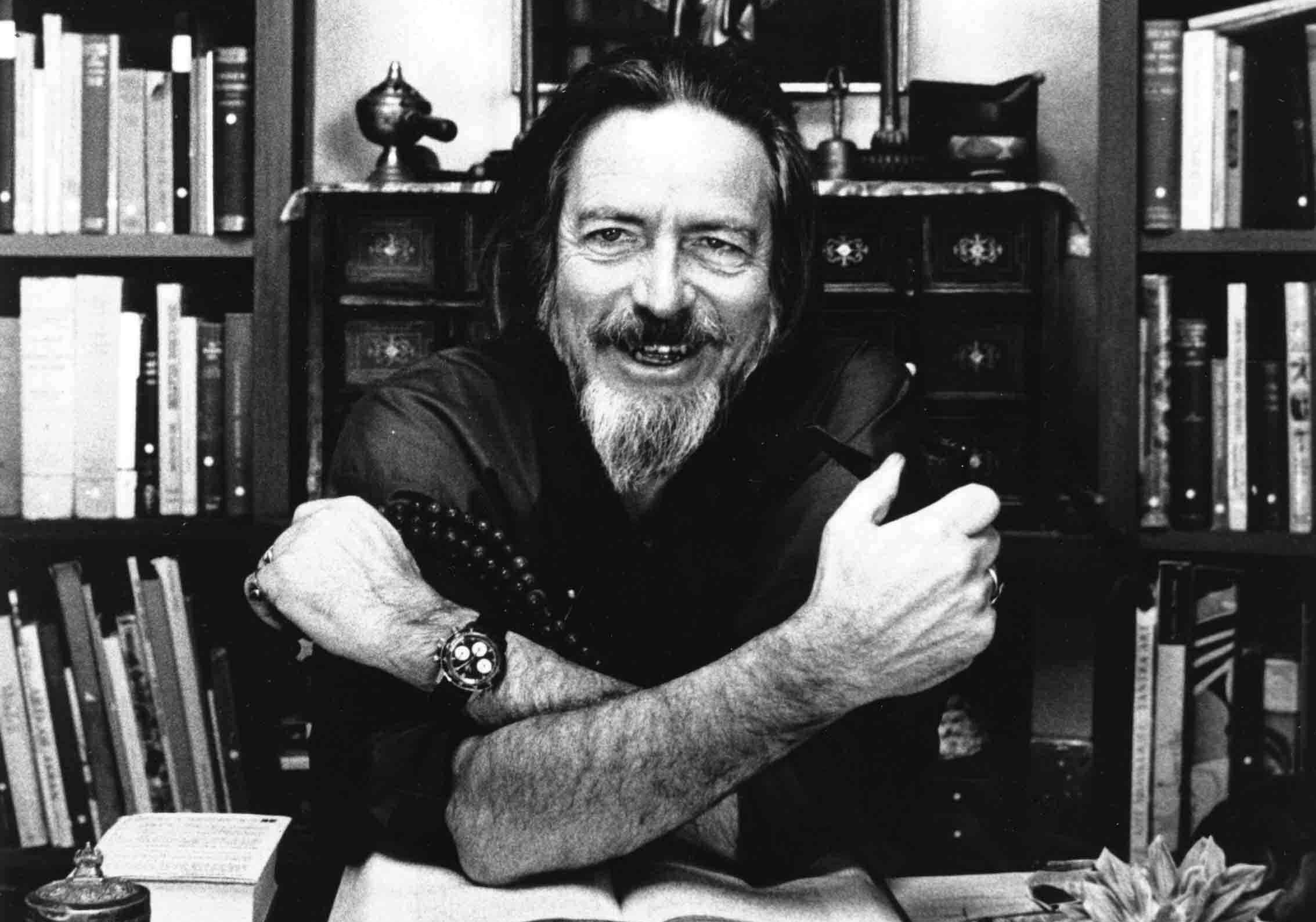

The piece that he making for Whim W’Him is inspired by Alan Watts, “his incredible teachings, and a what he said about how we choose what to do: “Choice is the act of hesitation that we make before making a decision.” (Perhaps Ihsan could easily have keyed on another Watts quote: The only way to make sense out of change is to plunge into it, move with it, and join the dance.) “I’m only now seeing where I can go with the piece,” since it had been only 3 days he’d been working with the dancers when we talked.

Ihsan says he used to be very structured in his approach to creation, “everything penciled out ahead of time. Then I came in and colored it, but that stifled creativity. When it’s a new company to me, and we don’t know each other’s quality, I want to see our reactions to each other—by doing that I get a much better result.” And, he adds, “I’m much calmer now than I used to be.” As to music or sound, he is still toying with ideas. Ludovico Einaudi perhaps? Maybe Jóhann Jóhannsson. The spoken words from Alan Watts definitely. This week, he’ll keep shifting music and see how it develops.

“Part of the beauty of this situation,” Ihsan muses, comparing qualities of the meditative experience to the years spent onstage, “is the bareness. It’s startling how familiar meditation was when I started it—no past and future, eliminating of audiences and technicians in the wings. I am very opposed to dancers ‘performing’ in what I’m doing (don’t get me wrong I love a good musical and those performers). It needs to have that honest approach. Then I’m touched. The audience too can be touched more directly. You find more…” than in more structured circumstances, such as when he has contracted to do a premiere in Germany, when he signed a year in advance and had already met with stage and set and costume design months ahead. By contrast, “When I come to this,” he says, “there is not the pressure, you have carte blanche to do whatever you want, within reason. I like to take the opportunity to play around and experience.” He pauses and says, “I would never ask dancers to do anything I would not have been willing to do myself.”

Of the Whim W’Him dancers, he says, “They are hard workers with great sense of humor. I like to work in a short, contained, totally focused period.” Taking the whole thing over-solemnly is not the same as taking it seriously, which it’s obvious he and they do. “You can’t have freedom if you’re obsessive. I love to laugh, I love to dance, the most freedom I feel is when I dance. A wholeness and a connection of body and mind.”